Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2008) |

| Pierre Teilhard de Chardin | |

|

|

| Born | May 1, 1881 Orcines, (France) |

|---|---|

| Died | April 10, 1955 (aged 73) New York, New York (USA) |

| Nationality | France |

| Fields | Paleontology, Philosophy |

| Known for | The Phenomenon of Man |

| Religious stance | Roman Catholic |

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (French pronunciation: [pjɛʀ tejaʀ də ʃaʀdɛ̃]; 1 May 1881, Orcines, France – 10 April 1955, New York City) was a French philosopher and Jesuit priest who trained as a paleontologist and geologist and took part in the discovery of Peking Man. Teilhard conceived the idea of the Omega Point and developed Vladimir Vernadsky's concept of Noosphere.

Teilhard's primary book, The Phenomenon of Man, set forth a sweeping account of the unfolding of the cosmos. He abandoned traditional interpretations of creation in the Book of Genesis in favor of a less strict interpretation. This displeased certain officials in the Roman Curia and in his own order who thought that it undermined the doctrine of original sin developed by Saint Augustine. Teilhard's position was opposed by his church superiors, and his work was denied publication during his lifetime by the Roman Holy Office. The 1950 encyclical Humani generis condemned several of Teilhard's opinions, while leaving other questions open. In 2009, the Pope praised Teilhard and his work.

Contents |

[edit] Life

[edit] Early years

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born in Orcines, close to Clermont-Ferrand, in France on May 1, 1881. "De Chardin" is a vestige of a French aristocratic title and not properly his last name. He was formally known as "Pierre Teilhard". He was the fourth child of a large family. His father, an amateur naturalist, collected stones, insects and plants, and promoted the observation of nature in the household. Teilhard's spirituality was awakened by his mother. When he was 11, he went to the Jesuit college of Mongré, in Villefranche-sur-Saône, where he completed baccalaureates of philosophy and mathematics. Then, in 1899, he entered the Jesuit novitiate at Aix-en-Provence where he began a philosophical, theological and spiritual career.

As of the summer 1901, the Waldeck-Rousseau laws, which submitted congregational associations' properties to state control, prompted some of the Jesuits to exile themselves in the United Kingdom. Young Jesuit students continued their studies in Jersey. In the meantime, Teilhard earned a licentiate in literature in Caen in 1902.

[edit] Jesuit training

| Society of Jesus | |

|

History of the Jesuits |

|

From 1905 to 1908, he taught physics and chemistry in Cairo, Egypt, at the Jesuit College of the Holy Family. He wrote "...it is the dazzling of the East foreseen and drunk greedily... in its lights, its vegetation, its fauna and its deserts." (Letters from Egypt (1905–1908) — Éditions Aubier)

Teilhard studied theology in Hastings, in Sussex (United Kingdom), from 1908 to 1912. There he synthesized his scientific, philosophical and theological knowledge in the light of evolution. His reading of L'Évolution Créatrice (The Creative Evolution) by Henri Bergson was, he said, the "catalyst of a fire which devoured already its heart and its spirit." His views on evolution and religion particularly inspired the evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky. Teilhard was ordained a priest on August 24, 1911, aged 30.

[edit] Paleontology

From 1912 to 1914, Teilhard worked in the paleontology laboratory of the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle, in Paris, studying the mammals of the middle Tertiary sector. Later he studied elsewhere in Europe. In June 1912 he formed part of the original digging team, with Arthur Smith Woodward and Charles Dawson, to perform follow-up investigations at the Piltdown site, after the discovery of the first fragments of the (fraudulent) "Piltdown Man." Professor Marcellin Boule (specialist in Neanderthal studies), who so early as 1915 astutely recognised the non-hominid origins of the Piltdown finds, gradually guided Teilhard towards human paleontology. At the museum's Institute of Human Paleontology, he became a friend of Henri Breuil and took part with him, in 1913, in excavations in the prehistoric painted caves in the northwest of Spain, at the Cave of Castillo.

[edit] Service in World War I

Mobilised in December 1914, Teilhard served in World War I as a stretcher-bearer in the 8th Moroccan Rifles. For his valour, he received several citations including the Médaille Militaire and the Legion of Honour.

Throughout these years of war he developed his reflections in his diaries and in letters to his cousin, Marguerite Teillard-Chambon, who later edited them into a book: Genèse d'une pensée (Genesis of a thought). He confessed later: "...the war was a meeting ... with the Absolute." In 1916, he wrote his first essay: La Vie Cosmique (Cosmic life), where his scientific and philosophical thought was revealed just as his mystical life. He pronounced his solemn vows as a Jesuit in Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, on May 26, 1918, during a leave. In August 1919, in Jersey, he would write Puissance spirituelle de la Matière (the spiritual Power of Matter). The complete essays written between 1916 and 1919 are published under the following titles:

- Ecrits du temps de la Guerre (Written in time of the War) (TXII of complete Works) – Editions du Seuil

- Genèse d'une pensée (letters of 1914 to 1918) – Editions Grasset

Teilhard followed at the Sorbonne three unit degrees of natural science: geology, botany and zoology. His thesis treated of the mammals of the French lower Eocene and their stratigraphy. After 1920, he lectured in geology at the Catholic Institute of Paris, then became an assistant professor after being granted a science Doctorate in 1922.

[edit] Research in China

In 1923 he traveled to China with Father Emile Licent, who was in charge in Tianjin for a significant laboratory collaborating with the Natural History Museum in Paris and Marcellin Boule's laboratory. Licent carried out considerable basic work in connection with missionaries who accumulated observations of a scientific nature in their spare time. He was known as 德日進 (pinyin: Dérìjìn) in China.

Teilhard wrote several essays, including La Messe sur le Monde (the Mass on the World), in the Ordos Desert. In the following year he continued lecturing at the Catholic Institute and participated in a cycle of conferences for the students of the Engineers' Schools. Two theological essays on "original sin" sent to a theologian, on his request, on a purely personal basis, were wrongly understood[citation needed].

- July 1920: Chute, Rédemption et Géocentrie (Fall, Redemption and Geocentry)

- Spring 1922: Notes sur quelques représentations historiques possibles du Péché originel (Notes on few possible historical representations of original sin) (Works, Tome X)

The church hierarchy required him to give up his lecturing at the Catholic Institute and to continue his geological research in China.

Teilhard travelled again to China in April 1926. He would remain there more or less twenty years, with many voyages throughout the world. He settled until 1932 in Tientsin with Emile Licent then in Beijing. From 1926 to 1935, Teilhard made five geological research expeditions in China. They enabled him to establish a first general geological map of China.

In 1926–1927 after a missed campaign in Gansu he travelled in the Sang-Kan-Ho valley near Kalgan (Zhangjiakou) and made a tour in Eastern Mongolia. He wrote Le Milieu Divin (the divine Medium). Teilhard prepared the first pages of his main work Le Phénomène humain (The Human Phenomenon).

Joined the ongoing excavations of the Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian as an advisor in 1926 and continued in the role for the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the Geological Survey of China following its founding in 1928.

He resided in Manchuria with Emile Licent, then stayed in Western Shansi (Shanxi) and northern Shensi (Shaanxi) with the Chinese paleontologist C. C. Young and with Davidson Black, Chairman of the Geological Survey of China.

After a tour in Manchuria in the area of Great Khingan with Chinese geologists, Teilhard joined the team of American Expedition Center-Asia in the Gobi organised in June and July, by the American Museum of Natural History with Roy Chapman Andrews.

Henri Breuil and Teilhard discovered that the Peking Man, the nearest relative of Pithecanthropus from Java, was a "faber" (worker of stones and controller of fire). Teilhard wrote L'Esprit de la Terre (the Spirit of the Earth).

Teilhard took part as a scientist in the famous "Croisiere Jaune" or"Yellow Cruise" financed by Andre Citroen in Central Asia. Northwest of Beijing in Kalgan he joined the China group who joined the second part of the team, the Pamir group, in Aksu. He remained with his colleagues for several months in Urumqi, capital of Sinkiang. The following year the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) began.

Teilhard undertook several explorations in the south of China. He traveled in the valleys of Yangtze River and Szechuan (Sichuan) in 1934, then, the following year, in Kwang-If and Guangdong. The relationship with Marcellin Boule was disrupted; the Museum cut its financing on the grounds that Teilhard worked more for the Chinese Geological Service than for the Museum[citation needed].

During all these years, Teilhard strongly contributed to the constitution of an international network of research in human paleontology related to the whole Eastern and south Eastern zone of the Asian continent. He would be particularly associated in this task with two friends, the English/Canadian Davidson Black and the Scot George B. Barbour. Many times he would visit France or the United States, only to leave these countries to go on further expeditions.

[edit] World travels

From 1927–1928 Teilhard stayed in France, based in Paris. He journeyed to Leuven, Belgium, to Cantal, and to Ariège, France. Between several articles in reviews, he met new people such as Paul Valéry and Bruno de Solages, who were to help him in issues with the Catholic Church.

Answering an invitation from Henry de Monfreid, Teilhard undertook a journey of two months in Obock in Harrar and in Somalia with his colleague Pierre Lamarre, geologist, before embarking in Djibouti to return to Tianjin.

"Monfreid and I, we did not have anything any more European", joked Teilhard. "Once we dropped anchor, at night, along the basaltic cliffs where the incense grew. The men were going by dugout to fish odd fishes within the corals. One day, Hissas sold us a kid goat with camel milk. The crew took this opportunity to 'dedicate' the ship. The old reheated Negro who served Monfreid in his whole adventures dyed with blood the rudder, the mast, the front part of the ship, then, later in the night, it was the song of the Qur'an in the medium of thick incense smoke."[citation needed] While in China, Teilhard developed a deep and personal friendship with Lucile Swan.[1]

From 1930–1931 Teilhard stayed in France and in the United States. During a conference in Paris, Teilhard stated: "For the observers of the Future, the greatest event will be the sudden appearance of a collective humane conscience and a human work to make."

From 1932–1933 he began to meet people to clarify issues with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, regarding Le Milieu Divin and L'Esprit de la Terre. He met Helmut von Terra, a German geologist in the International Geology Congress in Washington, DC. A few months later Davidson Black died.

Teilhard participated in the 1935 Yale–Cambridge expedition in northern and central India with the geologist Helmut von Terra and Patterson, who verified their assumptions on Indian Paleolithic civilisations in Kashmir and the Salt Range Valley.

He then made a short stay in Java, on the invitation of Professor Ralph van Koningsveld to the site of Java man. A second cranium, more complete, was discovered. This Dutch paleontologist had found (in 1933) a tooth in a Chinese apothecary shop in 1934 that he believed belonged to a giant tall ape that lived around half a million years ago.

In 1937 Teilhard wrote Le Phénomène spirituel (The Phenomenon of the Spirit) on board the boat the Empress of Japan, where he met the Raja of Sarawak. The ship conveyed him to the United States. He received the Mendel medal granted by Villanova University during the Congress of Philadelphia in recognition of his works on human paleontology. He made a speech about evolution, origins and the destiny of Man. The New York Times dated March 19, 1937 presented Teilhard as the Jesuit who held that the man descended from monkeys. Some days later, he was to be granted the Doctor Honoris Causa distinction from Boston College. Upon arrival in that city, he was told that the award had been cancelled.[citation needed]

He then stayed in France, where he was immobilized by malaria. During his return voyage in Beijing he wrote L'Energie spirituelle de la Souffrance (Spiritual Energy of Suffering) (Complete Works, tome VII).

[edit] Death

Teilhard died on April 10, 1955 in New York City, where he was in residence at the Jesuit church of St Ignatius of Loyola, Park Avenue. He was buried in the cemetery for the New York Province of the Jesuits at the Jesuit novitiate, St. Andrew's-on-the-Hudson in Poughkeepsie, upstate New York. In 1970 the novitiate was moved to Syracuse, New York (on the grounds of LeMoyne College) and the Culinary Institute of America bought the old property, opening their school there a few years later. However, the cemetery remains on the grounds. A few days before his death Teilhard said "If in my life I haven't been wrong, I beg God to allow me to die on Easter Sunday"[citation needed]. April 10 was Easter Sunday.

[edit] Controversy with Church officials

In 1925, Teilhard was ordered by the Jesuit Superior General Vladimir Ledochowski to leave his teaching position in France and to sign a statement withdrawing his controversial statements regarding the doctrine of original sin. Rather than leave the Jesuit order, Teilhard signed the statement and left for China.

This was the first of a series of condemnations by certain church officials that would continue until long after Teilhard's death. The climax of these condemnations was a 1962 monitum (reprimand) of the Holy Office denouncing his works. From the monitum:

"The above-mentioned works abound in such ambiguities and indeed even serious errors, as to offend Catholic doctrine... For this reason, the most eminent and most revered Fathers of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries as well as the superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers.".[2]

Teilhard's writings, though, continued to circulate — not publicly, as he and the Jesuits observed their commitments to obedience, but in mimeographs that were circulated only privately, within the Jesuits, among theologians and scholars for discussion, debate and criticism[citation needed].

As time passed, it seemed that the works of Teilhard were gradually returning to favor in the church. For example, on June 10, 1981, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli wrote on the front page of the Vatican newspaper, l'Osservatore Romano:

"What our contemporaries will undoubtedly remember, beyond the difficulties of conception and deficiencies of expression in this audacious attempt to reach a synthesis, is the testimomy of the coherent life of a man possessed by Christ in the depths of his soul. He was concerned with honoring both faith and reason, and anticipated the response to John Paul II's appeal: 'Be not afraid, open, open wide to Christ the doors of the immense domains of culture, civilization, and progress.[3]

However, shortly thereafter the Holy See clarified that recent statements by members of the church, in particular those made on the hundredth anniversary of Teilhard's birth, were not to be interpreted as a revision of previous stands taken by the church officials.[4] Thus the 1962 statement remains official church policy to this day.

Although some Catholic intellectuals defended Teilhard and his doctrine (including Henri de Lubac)[5], others condemned his teaching as a perversion of the Christian faith. These include Jacques Maritain, Étienne Gilson and Dietrich von Hildebrand.[6]

[edit] Teachings

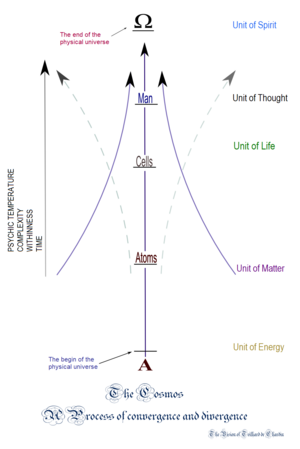

In his posthumously published book, The Phenomenon of Man, Teilhard writes of the unfolding of the material cosmos, from primordial particles to the development of life, human beings and the noosphere, and finally to his vision of the Omega Point in the future, which is "pulling" all creation towards it. He was a leading proponent of orthogenesis, the idea that evolution occurs in a directional, goal driven way. To Teilhard, evolution unfolded from cell to organism to planet to solar system and whole-universe (see Gaia theory). Such theories are generally termed teleological views of evolution.

Teilhard attempts to make sense of the universe by its evolutionary process. He interprets mankind as the axis of evolution into higher consciousness, and postulates that a supreme consciousness, God, must be drawing the universe towards him.

There is no doubt that The Phenomenon of Man represents Teilhard's attempt at reconciling his religious faith with his academic interests as a paleontologist.[7] One particularly poignant observation in Teilhard's book entails the notion that evolution is becoming an increasingly optional process.[7] Teilhard points to the societal problems of isolation and marginalization as huge inhibitors of evolution, especially since evolution requires a unification of consciousness. He states that "no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else."[7] This statement can effectively be seen as Teilhard's demand for unity insofar as the human condition necessitates it. He also states that "evolution is an ascent toward consciousness", and therefore, signifies a continuous upsurge toward the Omega Point, which for all intents and purposes, is God.[7]

Our century is probably more religious than any other. How could it fail to be, with such problems to be solved? The only trouble is that it has not yet found a God it can adore.[7]

[edit] Teilhard's phenomenology

Teilhard himself claimed his work to be phenomenology.

Teilhard studied what he called the rise of spirit, or evolution of consciousness, in the universe. He believed it to be observable and verifiable in a simple law he called the Law of Complexity/Consciousness. This law simply states that there is an inherent compulsion in matter to arrange itself in more complex groupings, exhibiting higher levels of consciousness. The more complex the matter, the more conscious it is. Teilhard proposed that this is a better way to describe the evolution of life on earth, rather than Herbert Spencer's "survival of the fittest." The universe, he argued, strives towards higher consciousness, and does so by arranging itself into more complex structures.

Teilhard identified what he termed to be different stages in the rise of consciousness. These stages are analogous to what are termed the geosphere and the biosphere. The Law of Complexity/Consciousness traces matter's path through these stages, as it 'complexifies' upon itself and rises in consciousness. Teilhard claimed that although it is not evident, consciousness (in an extremely limited degree) exists even in rocks, as the Law of Complexity/Consciousness implies. In plants, matter is complex enough to exhibit a consciousness that is the very life of the plant. In animals, matter is complex enough to an extraordinary degree to where consciousness shows itself in a wide range of reactionary movement to the whole universe.

However, Teilhard here proposed another level of consciousness, to which human beings belong, because of their cognitive ability; i.e. their ability to 'think'. Human beings, Teilhard argued, represent the layer of consciousness which has "folded back in upon itself", and has become self-conscious. Julian Huxley, Teilhard's scientific colleague, described it like this: "evolution is nothing but matter become conscious of itself."[citation needed]

So in addition to the geosphere and the biosphere, Teilhard posited another sphere, which is the realm of human beings, the realm of reflective thought: the noosphere.

In the noosphere Teilhard believed the same Law of Complexity/Consciousness to be at work, although not in a way previously seen. He argued that ever since human-beings first came into existence 200,000 years ago, the Law of Complexity/Conscious began to run on a different (higher) plane. Consciousness in the universe, he argued, now continues to rise in the complex arrangement and unification (Teilhard sometimes called it 'totalization'[9] of mankind on earth. As human beings converge around the earth, he reasoned, unifying themselves in ever more complex forms of arrangement, consciousness will rise.

Finally, the keystone to his phenomenology is that because Teilhard could not explain why the universe would move in the direction of more complex arrangements and higher consciousness, he postulated that there must exist ahead of the moving universe, and pulling it along, a higher pole of supreme consciousness, which he called Omega Point.

Teilhard re-interpreted many disciplines, including theology, sociology, metaphysics, around this understanding of the universe. A main focus of his was to re-assure the converging mass of humanity not to despair, but to trust the evolution of consciousness as it rises through them.

[edit] Influence of Teilhard

Teilhard and his work have a continuing presence in the arts and culture. He inspired a number of characters in literary works. References range from occasional quotations -- an auto mechanic quotes Teilhard in Philip K. Dick's A Scanner Darkly[10] -- to serving as the philosophical underpinning of the plot, as Teilhard's work does in Julian May's 1987–94 Galactic Milieu Series[11]. Teilhard also plays a major role in Annie Dillard's 1999 For the Time Being[12]. Characters based on Teilhard appear in several novels, including Jean Telemond in Morris West's The Shoes of the Fisherman[13] (mentioned by name and quoted by Oskar Werner playing Fr. Telemond in the movie version of the novel) and Father Lankester Merrin in William Peter Blatty's The Exorcist[14]. In Dan Simmons' 1989–97 Hyperion Cantos, Teilhard de Chardin has been canonized a saint in the far future. His work inspires the anthropologist priest character, Paul Duré. When Duré becomes Pope, he takes Teilhard I as his regnal name.[15] .

Teilhard's work has also inspired artworks such as French painter Afred Manessier's "L'Offrande de la terre ou Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin[16]" and American sculptor Frederick Hart's acrylic sculpture The Divine Milieu: Homage to Teilhard de Chardin[17]. A sculpture of the Omega Point by Henry Setter, with a quote from Teilhard de Chardin, can be found at the entrance to the Roesch Library at the University of Dayton[18]. Edmund Rubbra's 1968 Symphony No. 8 is titled Hommage a Teilhard de Chardin.

Teilhard's influence is commemorated on numerous collegiate campuses. A building at the University of Manchester is named after him, as are residence dormitories at Gonzaga University and Seattle University. His stature as a biologist was honored by George Gaylord Simpson in naming the most primitive and ancient genus of true primate, the Eocene genus Teilhardina.

The title of the short-story collection Everything That Rises Must Converge by Flannery O'Connor is a reference to Teilhard's work.

[edit] Bibliography

The dates in parentheses are the dates of first publication in French and English. Most of these works were written years earlier, but Teilhard's ecclesiastical order forbade him to publish them because of their controversial nature. The essay collections are organized by subject rather than date, thus each one typically spans many years.

- Le Phénomène Humain (1955), written 1938–40, scientific exposition of Teilhard's theory of evolution

- The Phenomenon of Man (1959), Harper Perennial 1976: ISBN 0-06-090495-X. Reprint 2008: ISBN 978-0061632655.

- The Human Phenomenon (1999), Brighton: Sussex Academic, 2003: ISBN 1-902210-30-1

- Letters From a Traveler (1956; English translation 1962), written 1923–55

- Le Groupe Zoologique Humain (1956), written 1949, more detailed presentation of Teilhard's theories

- Man's Place in Nature (1973)

- Le Milieu Divin (1957), spiritual book written 1926–27

- The Divine Milieu (1960) Harper Perennial 2001: ISBN 0-06-093725-4

- L'Avenir de l'Homme (1959) essays written 1920–52, on the evolution of consciousness (noosphere)

- The Future of Man (1964) Image 2004: ISBN 0-385-51072-1

- Hymn of the Universe (1961; English translation 1965) Harper and Row: ISBN 0-06-131910-4, mystical/spiritual essays and thoughts written 1916–55

- L'Energie Humaine (1962), essays written 1931–39, on morality and love

- Human Energy (1969) Harcort Brace Jovanovich ISBN 0-15-642300-6

- L'Activation de l'Energie (1963), sequel to Human Energy, essays written 1939–55 but not planned for publication, about the universality and irreversibility of human action

- Activation of Energy (1970), Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 0-15-602817-4

- Je M'Explique (1966) Jean-Pierre Demoulin, editor ISBN 0-685-36593-X, "The Essential Teilhard" — selected passages from his works

- Let Me Explain (1970) Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-061800-0, Collins/Fontana 1973: ISBN 0-00-623379-1

- Christianity and Evolution, Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 0-15-602818-2

- The Heart of the Matter, Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 0-15-602758-5

- Toward the Future, Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 0-15-602819-0

- The Making of a Mind: Letters from a Soldier-Priest 1914-1919, Collins (1965), Letters written during wartime.

- Writings in Time of War, Collins (1968) composed of spiritual essays written during wartime. One of the few books of Teilhard to receive an imprimatur.

- Vision of the Past, Collins (1966) composed of mostly scientific essays published in the French science journal Etudes.

- The Appearance of Man, Collins (1965) composed of mostly scientific writings published in the French science journal Etudes.

- Letters to Two Friends 1926-1952, Fontana (1968) composed of personal letters on varied subjects including his understanding of death.

- Letters to Leontine Zanta, Collins (1969)

- Correspondence / Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Maurice Blondel, Herder and Herder (1967) This correspondence also has both the imprimatur and nihil obstat.

- de Chardin, P T (1952), "On the zoological position and the evolutionary significance of Australopithecines", Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences 14 (5): 208–10, 1952 Mar, PMID 14931535

- de Terra; de Chardin; Paterson (1936), "Joint geological and prehistoric studies of the Late Cenozoic in India", Science 83 (2149): 233–236, 1936 Mar 6, doi:, PMID 17809311

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Aczel, Amir (4 November 2008). The Jesuit and the Skull: Teilhard de Chardin, Evolution, and the Search for Peking Man. Riverhead Trade. pp. 320. ISBN 978-1-95448-956-3.

- ^ Warning Considering the Writings of Father Teilhard de Chardin, Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, June 30, 1962.

- ^ Cardinal Agostino Casaroli praises the work of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin to Cardinal Paul Poupard, then Rector of the Institut Catholique de Paris - L'Osservatore Romano, June 10, 1981 @ TraditionInAction.org

- ^ Communiqué of the Press Office of the Holy See, English edition of L'Osservatore Romano, July 20, 1981.

- ^ De Lubac, Henri, Teilhard de Chardin: The Man and his Meaning, Hawthorn Books, 1965

- ^ Lane, David (1996). The Phenomenon of Teilhard: Prophet for a New Age. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0865544987.

- ^ a b c d e Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man (New York: Harper and Row, 1959), 250-75.

- ^ Kraft, R. Wayne (1983). A Reason to Hope: A Synthesis of Tieilhard de Chardin's Vision and Systems Thinking. Seaside, CA: Intersystems Publications. ISBN 091410514.

- ^ de Chardin, Teilhard (2003). The Human Phenomenon. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 172. ISBN 978-1902210308.

- ^ Dick, Philip K. (1991). A Scanner Darkly. Vintage. pp. 127. ISBN 978-0679736653.

- ^ May, Julian (April 11, 1994). Jack the Bodiless. Random House Value Publishing. pp. 287. ISBN 978-0517116449.

- ^ Dillard, Annie (2/8/2000). For the Time Being. Vintage. ISBN 978-0375703478.

- ^ Moss, R.F. (Spring, 1978). "Suffering, sinful Catholics". The Antioch Review 36 (2): 170-181. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4638026. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "Bill Blatty on "The Exorcist"". www.geocities.com. http://www.geocities.com/Hollywood/Lot/5160/blatty.html. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ Simmons, Dan (2/1/1990). The Fall of Hyperion. Doubleday. pp. 464. ISBN 978-0385267472.

- ^ "Liste des œuvres de Manessier dans les musées de France - Wikipédia". fr.wikipedia.org. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_%C5%93uvres_de_Manessier_dans_les_mus%C3%A9es_de_France. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "The Divine Milieu by Frederick Hart". www.jeanstephengalleries.com. http://www.jeanstephengalleries.com/hart-divine.html. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "UDQuickly Past Scribblings". campus.udayton.edu. http://campus.udayton.edu/udq/scribblings/0708scribblings.html. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Mary and Ellen Lukas, Teilhard (Doubleday, 1977)

- Robert Speaight, The Life of Teilhard de Chardin (Harper and Row, 1967)

- Dietrich von Hildebrand, Teilhard de Chardin: A False Prophet (Franciscan Herald Press 1970).

- Dietrich von Hildebrand, Trojan Horse in the City of God

- Dietrich von Hildebrand, Devastated Vineyard

- David H. Lane, The Phenomenon of Teilhard: Prophet for a New Age (Mercer University Press)

- Henri de Lubac, SJ, The Religion of Teilhard de Chardin (Image Books 1968)

- Henri de Lubac, SJ, The Faith of Teilhard de Chardin (Burnes and Oates 1965)

- Henri de Lubac, SJ, The Eternal Feminine: A Study of the Text of Teilhard de Chardin (Collins 1971)

- Henri de Lubac, SJ, Teilhard Explained (Paulist Press 1968)

- Christopher Mooney, SJ, Teilhard de Chardin and the Mystery of Christ (Image Books, 1968)

- Robert Faricy, SJ, Teilhard de Chardin's Theology of Christian in the World (Sheed and Ward 1968)

- George A. Maloney, SJ, The Cosmic Christ: From Paul to Teilhard (Sheed and Ward 1968)

- Robert Faricy, SJ, Teilhard de Chardin's Theology of Christian in the World (Sheed and Ward 1968)

- Robert Faricy, SJ, The Spirituality of Teilhard de Chardin (Collins 1981, Harper & Row 1981)

- Robert Faricy, SJ and Lucy Rooney SND, Praying with Teilhard de Chardin(Queenship 1996)

- Ursula King, The Spirit of Fire: The Life and Vision of Teilhard de Chardin (Orbis Books, 1996)

- Robert J. O'Connell, SJ, Teilhard's Vision of the Past: The Making of a Method, (Fordham University Press, 1982)

- Amir Aczel, The Jesuit and the Skull: Teilhard de Chardin, Evolution and the Search for Peking Man (Riverhead Hardcover, 2007)

- Claude Cuenot, Science and Faith in Teilhard de Chardin (Garstone Press, 1967)

- Andre Dupleix, 15 Days of Prayer with Teilhard de Chardin (New City Press, 2008)

[edit] External links

[edit] Favourable to Teilhard

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Teilhard de Chardin |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Pierre Teilhard de Chardin |

- Teilhard - Man of the Millennium?

- (French) Official Site Teilhard de Chardin Foundation

- Teilhard de Chardin – The American Teilhard Association homepage

- Brief profile from Fairfield University

- The Human Phenomenon – an excerpt from The Phenomenon of Man

- A Globe, Clothing Itself With a Brain from WIRED magazine, June, 1995

- Is Noogenesis Progressing? – 2002 essay

- Human Evolution Research Institute

- Noetic Art – based on quotes from Teilhard's Human Energy

- Catholic church newspaper, l'Osservatore Romano, June 10, 1981*

- Wilfrid Desan

[edit] Unfavourable to Teilhard

- Catholic church monitum (warning) in 1962, on the writings of Teilhard de Chardin

- Review of The Phenomenon of Man by biologist Peter Medawar, from Mind, N.S., 70 (1961):99-106.

- 1989 review of Wolfgang Smith's Teilhardism and the New Religion, an analysis and refutation of the teachings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

- Teilhard, Darwin, and the Cosmic Christ –autumn 1999 newsletter, Southern Papist Perspective

- Sean Hyland, Teilhard de Chardin: Rogue Theologian (establishing that the condemnations still stand)

[edit] Other

- Teilhard and the Piltdown hoax – from May 1981 Antiquity refuting S J Gould's conjecture in The Panda's Thumb that Teilhard was involved in the Piltdown hoax

- Is Teilhard Off the Hook? – from Science 83 also dismissing Gould's claim

- "Cyberspace and the Dream of Teilhard de Chardin" from summer 1994 Creation Spirituality magazine

- Piltdown Man 1997 essay from TalkOrigins Archive considering many suspects and also exonerating Teilhard

- The Teilhard Page

- Works by or about Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||