Memories Of E. Lucy Braun

Lucile Durrell

1981. Ohio BioI. Surv.

BioI. Notes No. 15

In

the mid-1930's, Richard, my husband, and I were geology students at the

University of Cincinnati where we took three botany courses from a marvelous

teacher, E. Lucy Braun. The first course was world botany in which we roamed

the world from pole to equator. Next was geographic botany in which we studied

the vegetational types in the United States. The

third course was plant succession, using the communities in the Cincinnati

region together with their changes as our laboratory. Lucy illustrated many of

her lectures with superior slides of her own taking.

world botany in which we roamed

the world from pole to equator. Next was geographic botany in which we studied

the vegetational types in the United States. The

third course was plant succession, using the communities in the Cincinnati

region together with their changes as our laboratory. Lucy illustrated many of

her lectures with superior slides of her own taking.

These courses have added immeasurably to our appreciation

of the earth. An important part of our travel experience is our awareness of

the vegetation. Facts learned so long ago jump into our minds, for example, the

drip lips of leaves in tropical rain forests, the wide spacing of desert

plants, and the vivid blue of alpine plants. After all that Lucy had taught us,

what a thrill it was to see our first baobab tree, the flat top acacias of the

African savanna, or the myriad species of eucalyptus in Australia. Although

there was little talk about land conservation in those early years, Lucy

planted the seeds of awareness and concern in her students. Her interest and

knowledge inspired the creation of the nature preserve system in Adams County,

Ohio, beginning in 1959 with 42 acres (16.8 ha) for Lynx Prairie, a system that

has now grown to over 3000 acres (1200 ha).

Lucy's teaching continued long after her early

retirement. Professional scientists, such as Jane L. Forsyth at Bowling Green

State University, came to her for help and advice. Jane told me that Lucy

wanted to shift the glacial boundary slightly in southwestern Ohio on the basis

of her knowledge of the distribution of plants. Amateurs who wished to know

something about species and where to find them came to her. One of those

individuals is a well-known Cincinnatian who has given generously to help The

Nature Conservancy with land acquisition in Adams County. This person said,

"She introduced me to all the plants. She showed me how to use a hand

lens; she opened up a whole new world for me. From her I learned so many things

about nature." This same admirable woman has recently deeded her estate

overlooking the Ohio River to the Hamilton County Parks and her wonderful woods

will become a nature preserve.

In 1969 at the age of 80, Lucy assisted the Woman's

Committee of the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History in planning a short-term

adult course. She gave two of the lectures, and assisted by Richard, led a

field trip to Roosevelt Lake in Scioto County, Ohio, for over 80 people.

Another active conservationist, a learning companion on

field trips with Lucy in her latter years, described Dr. Braun as a very lively

lady. On one excursion in search of trailing arbutus, they scurried up a steep

slope in the Shawnee State Forest. However, both Lucy and her sister, Annette said

nothing when they found the arbutus, allowing this friend to have the delight

of her own discovery of the plant.

Lucy was born in 1889, five years later than her sister,

Annette. Their parents were exceedingly strict and protective. Her mother, a

retired teacher, taught Lucy at home for the first three years.

Annette by her 30's had already established a reputation

as a microlepidopterist, but parental supervision

continued. One time a staid and well-respected colleague came from out-of-town to

consult with Annette. Her father, a school principal, said, "You may have

one hour with my daughter." During that whole time he sat on a chair outside

the open door.

Their parents took the two girls by horse-drawn streetcar

to the woods in Rose Hill, now apart of Avondale, and Lucy began collecting and

pressing plants during her high school years. Throughout her life she made an

extensive herbarium, which now resides at the National Museum in Washington, D.

C.

As the neighborhood changed following their parents'

death, the two little old maids were mocked and teased by young boys. Life

became unbearable and it was necessary to leave their old-fashioned, narrow

house in Walnut Hills and find a new home.

In 1943 Lucy purchased two acres (0.8 ha) with a

spacious and beautiful limestone house on Salem Road, a drive that winds up

from the Ohio valley to Mt. Washington. A wonderful large-paned window in the

dining room looks out to the majestic trees that surround the house. Into this

woods with a rich herbaceous flora Lucy introduced numerous native plants, many

from the Appalachians. Luckily, her land lay on leached Illinoian

glacial deposits so the acid-loving plants nourished.

Richard and I would receive a call from Lucy,

"Come, you must come; the red azalea of the Cumberlands

is in bloom." It was a summons and dutifully we would go. She took great

pride in the Magnolia ashei

that she had started from seed collected in western Florida.

In this tranquil setting the two sisters lived serenely,

surrounded by their Victorian furniture, which took on beauty in their new

home. Befriended and helped by their neighbors, the Brauns

became a source of pride to Mt. Washington, where they were known as the two

lady doctors.

Their social life was limited. Occasionally they

entertained with a slide show, always with an intermission for lemonade and

cookies. For visiting scientific peers, I only recently learned, to my

surprise, that they had the simplest of suppers.

Both ladies enjoyed their many western motor trips.

Lucy, the photographer, took hundreds of slides, labeled by date, place, time,

and direction. Her only relaxation at home was her plants and her mystery

stories. When a friend expressed surprise, she retorted, "Why, all

scientists read mysteries."

Annette, who had assisted Lucy in all phases of her

life, bloomed after Lucy's death. For the first time in 87 years, she made the

decisions. One day she proudly proclaimed, "I made a coffee cake this

morning." Annette, although missing her sister dreadfully, lived in their

home for five more years. In 1976 it was necessary to move her to a nursing

home, and she sold the house to DeVere Burt, Director

of the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. Annette died 27 November 1978 at

94. She was a remarkable lady in her own right.

At Iowa State University, DeVere

had been fully exposed to Lucy's book, The

Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America, and to her studies in ecology.

When he came to Cincinnati, he found it a thrill to rub elbows with E. Lucy

Braun. He still experiences nostalgia when walking through the garden where she

nurtured so many plants. With Annette's help from her nursing home, he kept a

log of the blooming dates of the plants. DeVere still

tends the coleus and the begonia plants, some of which are over 100 years old,

continuing the sisters' ritual of taking slips in the fall. A forsythia planted

by their mother in 1850 on May Street and moved to Mt. Washington in 1943 still

blooms beneath the kitchen window. Her mother's primroses still flower at the

edge of the woods, which border the front yard.

DeVere considers it the greatest honor

to live in her house. Guests in the natural science field who come to visit are

honored to know that they are sleeping in the home of E. Lucy Braun. For her

they hold a reverential Feeling.

Field trips were very much a part of Lucy and Annette's

lives: Annette was usually her companion. They first went to Adams County on

the Norfolk and Western Rail road and stayed at an old-fashioned spa in Mineral

Springs. In her early studies she took her students with her for a week to make

transects and plot studies.

One of these early students tells that the scheduled

entertainment one evening was a fungi watch. Lucy and the students climbed the

hill behind the hotel and waited for darkness to fall. It became perfectly

dark, but to Lucy's dismay, the species down slope identified earlier as

phosphorescent did not glow as she had predicted. When she went down the hill

to investigate, she found, to her chagrin, that the fungus was glowing only on

the underside.

Lucy could not be fooled about the many native plants,

for her knowledge was encyclopedic. She also had total recall of all her trips,

their dates, what plants she had seen and where. On request she could give you

the exact directions for the location of a certain species in such detail as

"40 feet [12 m] southwest from the big beech."

After 1930 when Lucy bought her first car, she and

Annette made many trips to the Kentucky mountains.

While walking in the hills during prohibition, moonshiners posed a serious

problem. It was hill protocol never to approach a still. Luckily the ladies never

had a direct confrontation. Local residents warned them of locations; sometimes

the calls of the moonshiners alerted them to danger or even the lookout men

directed them away from the stills.

The Braun sisters got along well with the suspicious

mountain people because they heeded the local customs. They made friends and

they never tattled on the moonshiners. They often rode the logging trains to

remote areas. One day, while attempting to climb Big Black Mountain in Kentucky,

they approached a mountain cabin where they had been told a trail started. When

Lucy asked the woman where the trail took off, the woman replied, "There's

no trail up Big Black Mountain. It's too overgrown, too steep; you would never

make it from here." The two sisters stayed a little longer, chatting.

Suddenly the light in the woman's eyes turned friendly, "Oh, you' re the

plant ladies living with the Mullins family. You're the ladies that take pictures

of trees. Come along, I'll show you the trail."

One day in the Natural Bridge area in Kentucky, Annette

and Lucy were returning to the lodge late in the day by a different way than

they had gone. They suddenly sensed they were approaching a still, so they retreated

over the divide into another valley where Lucy remembered ten years before she

had used a wooden ladder to climb up over the steep sandstone rim. The ladder

was gone. It was necessary to make a wide detour and they did not reach the lodge

until 9:30 pm, well after dark, much to the relief of the management. It would

be interesting to know how many miles these sisters walked in pursuit of Lucy's

plants. Annette said they walked 24 miles (38.4 km) on one long day.

Lucy's field trips continued almost to her death. Her

last long excursion was to Carter Caves, Kentucky, in 1970: she died a year

later. In the last year or so her vigor was gone. She walked slowly stopping

often. I remember she told Richard, " I can't go with everybody now, but

you are willing to go slowly enough."

Thanks did not come easily to Lucy's lips: instead, she

could be blunt and ungracious. A delicious soup brought during her illness

prompted. " I don't like it, take it back." A lovely pink blanket

initialed by a friend especially for her fared equally, " I don't need it,

take it back." Only now do I realize that Lucy did sometimes show appreciation,

although not often. Despite her idiosyncrasies, she had a wide circle of

friends: notable scientists from the University of Cincinnati, her students,

and nonprofessionals. Known and admired by botanists in her field, she carried

on an active correspondence often feuding with them if they opposed her views.

These letters are all on file at the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History,

where DeVere Burt hopes to research them for a future

paper. Elizabeth Brockschlager, a retired schoolteacher

and proficient botanist of Cincinnati, has kept a collection of personal

letters written about Lucy's trips.

She was admired and respected by her students, a number

of whom went on to develop careers in botany. Many were faithful to the end.

However, one noted botanist commented, "She treated me like a sophomore

until she died." In the early 1920's, Dr. Braun sparked the university

botany club, The Blue Hydra, to raise money to purchase the botanical preserve

of Hazelwood for the university. The students organized moneymaking projects

and asked for donations. They sold homemade candy on Tuesdays and Thursdays to

the engineers. How different from today; now someone would ask for a grant.

Lucy might be characterized by

four D's and an F:

dedication. determination,

domination, demanding, and frugal.

She was dedicated to plant science,

to her department to which she brought renown, and to land preservation. It was

she who brought the attention of The Nature Conservancy to Adams County. How

well l remember Lucy in April of 1967 leading a group of Cincinnatians over the

shoulder of Whip-poor-will Hill to an elbow of capture and on to the one of two

stations for Pachystima canbyi in

Ohio. All of this land is now part of The Wilderness Preserve and four of that original group have been generous contributors.

The second D is for determination.

A former student tells this story. Moving into a new office in Old Tech

Building, Dr. Braun found the room on the ground floor unbearably hot. A call

to the maintenance department brought no results. It then became her policy

each morning when she arrived to take a temperature reading and call

maintenance. "This morning my room is 100 degrees," The next day

another call, "My office is 98 degrees." This pattern continued for

several weeks and finally the head of maintenance replied, "All right, all

right," but then she heard him say, "Go up and wrap those steam pipes

in Old Tech and shut that blankety-blank woman

up."

A story is told of how she intimidated a member of the

Ohio Flora Committee when some changes were suggested for The Woody Plants of Ohio. She was determined

that her way was the only way, and she set up such a tantrum that the member

retreated saying. "What can I do?"

Her strong will appeared on field

trips even with adults. One would eat where Lucy wanted to eat, one would rest

where Lucy wanted to rest, and she was always in complete charge. She was

determined that no fire should ever touch the prairie patches in Adams County.

She believed the rocky soil was too shallow to withstand burning. Dr. Warren A.

Wistendahl of Ohio University innocently asked what

she thought about the management of preserves. She launched into a heated

attack on the practice of burning for Adams Count y. It was indeed a scorching

reply.

The third D is for domination.

Lucy, the bread-winner, was particularly dominating

towards her sister who served as housekeeper. Annette was a renowned authority

in entomology, but she did her research at home. Lucy was in complete command.

She would say, " Annette, get me that book" or "Annette, go find the map." It was

hard sometimes not to rebuff Lucy's treatment of her sister, but I always held

my tongue. Dr. Milton B. Trautman commented. "She

was the only person in the world with whom I usually kept my mouth shut."

As for the last D, she was demanding of her students, requiring a complete report after every

field trip, and of her illustrator, Bettina Dalve.

Having never done any botanical drawings when Lucy approached her to do the

drawings for The Woody Plants of Ohio.

Bettina started with the low price of $1.50 an hour. Evidently, Dr. Braun was

satisfied with her work since Bettina illustrated the whole book. When Dr.

Braun asked Bettina to do The Monocotyledoneae: Cat-tails to

Orchids,

Bettina replied, "I can't possibly do them at that price," Lucy

answered, "I wondered when you would ask."

It was Dr. Braun's practice to bring a fresh plant and

written instructions concerning the essential details to be sketched. Bettina

marveled at the clarity of these words, particularly in how effectively they

communicated to her, a nonbotanist. She could easily follow Lucy's

instructions. Lucy spoke glowingly of the drawings to others, but Bettina

waited eight and one-half years hoping for some sign of appreciation, but none

ever came even after the wide public acclaim accorded the two books.

Bettina commented that, "She was a very difficult

woman to work for. The manner of disdain with which she treated my mother who

did all the layouts was especially hard for me. Mother was a talented artist

and Dr. Braun behaved like an intellectual snob." Bettina recounts how she

and her husband returned from a long western trip hot, tired and dirty. Lucy

Braun was waiting on the porch steps, plant in hand,

demanding an immediate sketch. Bettina complied.

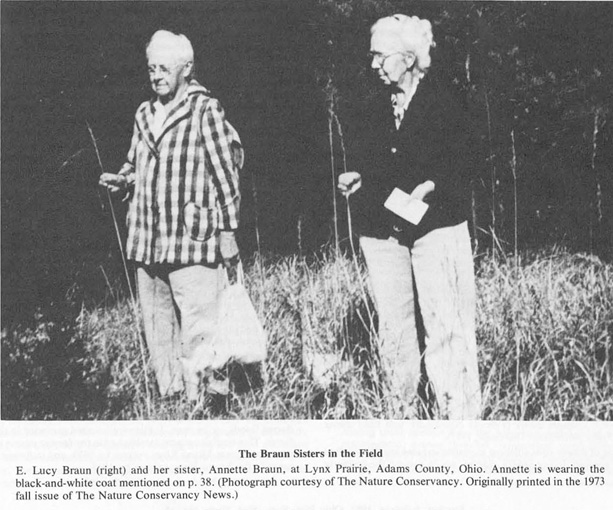

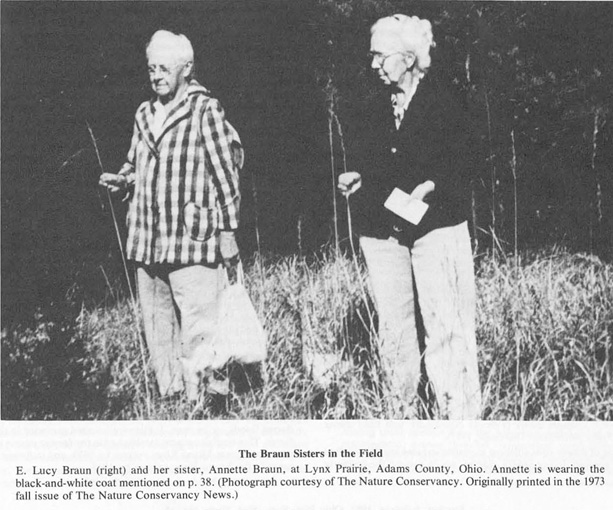

The F is for frugal.

The two sisters were exceptionally frugal. One day in the field I admired a

black-and-white wool coat that Annette was wearing. "Oh yes," she

said,'" bought it in 1913." I gasped in amazement: that was before I

was born. The coat was then already well over 50 years old.

When time came for friends to break up the house, their

saving ways came into even sharper focus. Many packages from their May Street

moving, about 30 years before, still remained wrapped: three coat hangers labeled

"3 rusty hangers" and a package labeled "2 good empty boxes." Numerous

small gifts still remained in their boxes.

Lucy was free to give criticism, but she did not take it

with grace. The Kenneth Casters of the University of Cincinnati tell about an incident

when a micropaleontologist came to lecture in the

Geology Department. Because this lecture was after Lucy's retirement the newer

students in attendance knew nothing of E. Lucy Braun. To them the two white-haired

sisters appeared like two characters out of "Alice in Wonderland." As

the lecture continued, challenging Dr. Braun's origins of the mixed mesophytic forest, Lucy's lips grew tighter and tighter.

When the speaker sat down she rose to battle and made a ferocious attack upon

him, which was followed by a vast silence that filled the room. Finally, the

speaker arose and said. "Thank you, Dr. Braun, I wanted to hear your

opinion."

Lucy was the master of the "put-down." To me,

when I mentioned a new and delicious cookie recipe, " Oh, I couldn't waste

my time on that sort of thing." Or to Marion Becker, author of The Joy of Cooking, a creative person

who led several exciting lives in conservation, promoting the arts, and creating

a wonderful wildflower garden, " How can you fritter away your time on all

those different things?" To her sister who might wan t to show a friend

some new drawings of her moths, "Oh, they don't want to see pictures of

your old bugs."

Many years ago Dr. Milton B, Trautman

observed the peculiarity of the skunk cabbage in which the pistillate

portion of the flower is mature before the pollen is ready. Excited that he had

found something rare in nature, he told Lucy of his discovery. Lucy very

quickly pricked his balloon of elation by a terse comment. "Not at all, not at

all uncommon."

Lucy had a strong self-image. In 1956 she was included

in the 50 most outstanding botanists by the Botanical Society of America. When

I asked Annette for Lucy's reaction she answered, "Why she didn't say

anything. She knew she deserved it." Annette also commented that her

sister considered The Deciduous Forests

of Eastern North America her crowning achievement.

Kenneth Hunt, former Professor of Botany at Antioch

College, gave me this thumbnail sketch: "a mild-mannered, gentle person,

confident and sure, a woman of steel, a master of her craft, quiet, absolute."

I can agree with all, except perhaps the "gentle."

Annette spoke of her sister only with admiration and

affection. Lucy respected her opinion and Annette played an important role in

the writing of Lucy's books. The cooperation appears one-sided: Lucy's

contribution to Annette's research was the identification of the food plants of

her moths. When they carried on a joint conversation, one sister would start a

sentence and the other would finish it.

We visited Lucy several times in her last three months as she grew weaker. As she lay wan upon her bed,

Richard and I sat beside her while she plotted strategy to help save the Red

River Gorge in Kentucky. Her mind was clear.

Lucy was born a Victorian, and she died a Victorian in

1971 at 82 years of age. Times change, but she did not change. We marvel now at

a life so full of significant scientific achievement. Our lives and those of

many others are richer and fuller because of E. Lucy Braun.

E. Lucy Braun is still generating stories. She was known

to a number of garden clubs in Cincinnati, many of whom

contributed money to the projects in Adams County. After her death the ladies

were accustomed to calling her the late E. Lucy Braun. One young woman

inquired, "Who is this Lady Braun, is she from England or

somewhere?" Say it fast, the late E. Lucy Braun. I know Emma Lucy Braun is

pleased that she has entered into the nobility.

REFERENCES

Additional information with photographs on the life of

E. Lucy Braun is contained in the following articles:

Fulford, Margaret, William A. Dreyer,

and Richard H. Durrell. 1972. Memorial to Dr. E. Lucy Braun. p. 3-5. In 1967. E. Lucy

Braun. Lynx Prairie. The E. Lucy Braun Preserve, Adams County. Ohio: A tract of

53 acres acquired by The Nature Conservancy and deeded to the Cincinnati Museum

of Natural History. Cincinnati Mus. Nat. Hist., Cincinnati, Ohio. [16 p.]

Peskin, Perry K. 1979. A walk through Lucy Braun's prairie. The Explorer 20(4):

15-2 1.

Stuckey, Ronald L. 1973. E. Lucy

Braun (1889-1971), outstanding botanist and conservationist: A biographical

sketch with bibliography. Mich. Bot. 12:83-106.

world botany in which we roamed

the world from pole to equator. Next was geographic botany in which we studied

the vegetational types in the United States. The

third course was plant succession, using the communities in the Cincinnati

region together with their changes as our laboratory. Lucy illustrated many of

her lectures with superior slides of her own taking.

world botany in which we roamed

the world from pole to equator. Next was geographic botany in which we studied

the vegetational types in the United States. The

third course was plant succession, using the communities in the Cincinnati

region together with their changes as our laboratory. Lucy illustrated many of

her lectures with superior slides of her own taking.