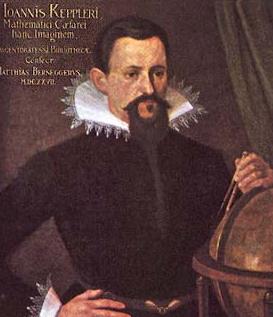

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), a German who went to Prague

to become Brahe's assistant.

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), a German who went to Prague

to become Brahe's assistant.

Unlike Brahe, Kepler truly believed in the Copernican system, but he also

felt the universe would somehow show mathematical beauty or symmetry.

Arguing in a way that Pythagoras and Plato would have sympathized with,

he suggested that the orbits might be arranged as

regular polygons (triangles, squares, etc.).

Unfortunately Kepler (who described himself as a little lap dog)

was barking up the wrong tree.

Unlike Brahe, Kepler truly believed in the Copernican system, but he also

felt the universe would somehow show mathematical beauty or symmetry.

Arguing in a way that Pythagoras and Plato would have sympathized with,

he suggested that the orbits might be arranged as

regular polygons (triangles, squares, etc.).

Unfortunately Kepler (who described himself as a little lap dog)

was barking up the wrong tree.

However, Kepler did ask other, more fruitful, questions concerning the planetary orbits: why did the outer planets move more slowly? Saturn's orbit is about twice the size of Jupiter's, but Saturn takes substantially more than twice as long to go once around. He was bent on getting a hold of Brahe's data, which he felt would confirm his picture of the solar system. As luck would have it, Brahe asked Kepler to join his group in 1600, based on seeing Kepler's work in his rather mystical book, Mysterium Cosmographicum .

It would not be so easy to use Brahe's masses of data. Brahe was very secretive: he had his own agenda, which was to establish his own model of the solar system! Moreover, Brahe was not anxious for his data to be used to support a Copernican model. Brahe suggested he work on the orbit of Mars, one of the least circular orbits, for which Brahe would be obliged to give him a substantial amount of data. Brahe hoped it would occupy Kepler while Brahe worked on his theory of the Solar System. Kepler made a bet that he would understand the orbit in eight days. It took him eight years. However, it was precisely the Martian data that allowed Kepler to formulate the correct laws of planetary motion, thus eventually achieving a place in the development of astronomy far surpassing that of Brahe.

Who died and left you the Boss?

As luck would have it (for Kepler) in just the next year,

1601, Brahe's lifestyle caught up with him.

He became very ill at a banquet, and died a few days later of a

bladder infection. Kepler acted quickly, despite the uprising

of Brahe's family, to `take the observations under his care'...

To his credit, Kepler did publish the Rudolphine Tables of planetary positions in 1627, the crowning achievement of Tycho Brahe's career.