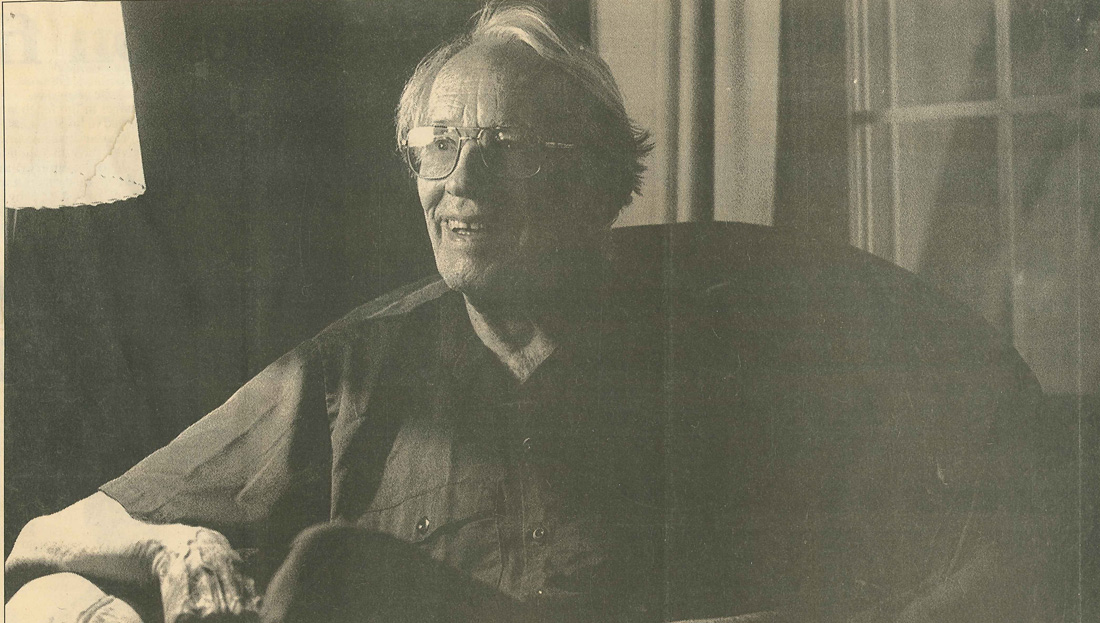

William F. Jenks

Port man honored as father of Peruvian

geology

By Sonya Vartabedian

Newburyport, MA

Daily News

October 1997

To

many, they are mere lumps of mass. Something to be stepped on,

climbed over or hauled away. But when William Jenks uncovers a rock, he almost

always stops to take a closer look. And he doesn't leave until he's learned its

story. Jenks has made rocks and minerals his business for most all of his 88

years. As a geologist, he's gone prospecting mines and digging the soil in

Peru, Japan, Norway, Italy and even his own back yard.

"Just pick up a rock and it gives

you a look into the past. You can learn how it was formed and when it was

formed," said the now-retired Jenks who makes his home in Newburyport. "It's

not just a piece of stuff. It's a rock. It has a history."

It was in the undeveloped region of

southern Peru that Jenks made his geologic mark. Traveling by burro and mule into

unchartered areas with a hammer and some rope, the tall, lean man surveyed the

underground. His work doing the initial mapping of the strata in the region

surrounding Arequipa in the early 1940s earned him recognition as the father of

Peruvian geology. Last month, the Universidad de San Agustin in Arequipa named

a new geology studies building in his honor. He and several other geologists

who followed in his footsteps were also awarded honorary doctorates in geology from

the college.

Joined by two of his three daughters,

Jenks returned to Peru to attend the ceremonies, which were held during the Ninth

Peruvian Geology Congress in Lima. A modest man, he was almost embarrassed by

the attention, including requests for autographs from current students, who

presented him with a silver platter. "I was surprised," he said,

"to be honored after all this time."

A special symbol

The daily paper in Lima praised him in an

editorial. As the first geologist to do systematic regional studies in Peru, the

paper said, the study of geology in the country is divided into two phases -

before and after Jenks. "He converted the (Universidad de San Agustin)

geology school into a myth and a special symbol in southern Peru," wrote

the paper. "Without doubt, he influenced the geology school over various

generations of students."

Like most children, Jenks enjoyed

collecting rocks and minerals in the town just outside Philadelphia where he grew

up. But when he left for Harvard University, he intended to pursue a career in

medicine like his father. The problem was that he wasn't fond of dissecting

things and hated the smell of formaldehyde. Geology, however, intrigued him. After

receiving both his bachelor and doctoral degrees from Harvard, Jenks went to

work for an oil company in Denver. A three-year contract with a mining company in

southern Peru was offered in 1938. He packed up his family and headed to South

America.

Jenks knew little Spanish, but he knew

geology. He initially worked in copper mines, but was then put in charge of explorations

for new mines. He would leave behind his late wife, Betty, and daughters for

weeks at a time as he explored dry, mountainous areas separated by small

pockets of communities. On occasion, Jenks would take students from the

university out of the classroom and into the field, giving them their first

chance to get their hands dirty. "They were studying geology out of books.

That's no way to learn it," he said. "If you really want to find out

details, really learn what happened, you have to get out there and look at it

on the ground. "You have to handle the rocks, look at the rocks, handle the

landscape to see what you can tell."

After his contract with the mining

company was up, the U.S. State Department offered him a one-year professorship at

Universidad de San Agustin, where he continued to hold classes in the field.

There were very few students then. Today, about 800 geology students are

enrolled in the school. Jenks stayed on for two more summers after his year of teaching,

venturing into northern Peru with a focus on petroleum and doing more

exploration work. In 1948, he published the "Geology of the Arequipa

Quadrangle," which served as the basis of the geologic work to follow in

the country.

A desire to explore

Upon returning to the United States,

Jenks continued to teach, first at the University of Rochester in New York and then

at the University of Cincinnati. But he never lost his desire for travel and exploration.

He spent a year teaching at the University of Tokyo on a Fulbright Scholarship

and was also invited to lecture at universities in Norway and Italy.

His keen curiosity of volcanoes led him

to Japan and then to Italy, where he journeyed to the summit of Mt. Vesuvius and

climbed part way up Mt. Etna in Sicily, the country's highest peak. It wasn't

until 1979, at the age of 70, that he retired. Three years later, he and his

wife moved to Newburyport to be closer to their daughters, one of whom lives in West Newbury. He keeps a collection of rocks

and minerals - mementos from his travels - in the kitchen of his Munroe Street house.

There's a piece of pyrite, an iron sulfide that he discovered in southern

Italy, and a specimen of fluoride that he retrieved in Illinois.

While students today may be more

interested in the environment and other fields, Jenks believes everyone should have

some understanding of geology and how the earth was developed. Unfortunately,

he said, most people take their surroundings for granted. "I like to have

people understand what they're looking at," he said. "Everywhere you

walk, even along the beach; there's geologic action there. "It would be

very hard for me to imagine driving through the Colorado Rockies and not

understanding how those mountains were formed."